- Home

- Larry Tagg

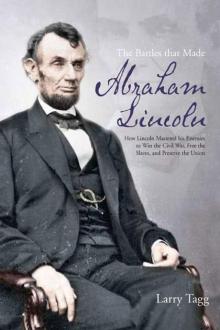

The Battles that Made Abraham Lincoln

The Battles that Made Abraham Lincoln Read online

© 2012 by Larry Tagg

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

First edition, first printing

Tagg, Larry.

The Battles That Made Abraham Lincoln: How Lincoln Mastered his Enemies to Win the Civil War, Free the Slaves, and Preserve the Union / Larry Tagg. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61121-126-9

ePUB ISBN: 9781611211276

1. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865. 2. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865—Public opinion. 3. United States—Politics and government—1861-1865. 4. Public opinion—United States. 5. Presidents—United States—Biography. I. Title.

E457.15.T15 2012

973.7092—dc23

2012039015

Previously published in hardcover as The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln: The Story of America’s Most Reviled President, by Larry Tagg (ISBN: 978-1-932714-61-6 / 2009)

Savas Beatie LLC

989 Governor Drive, Suite 102

P.O. Box 4527

El Dorado Hills, CA 95762

Phone: 916-941-6896

(E-mail) [email protected]

Savas Beatie titles are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more details, contact Savas Beatie Special Sales, P.O. Box 4527, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762, or you may e-mail us directly at [email protected], or jump over to our informative website at www. savasbeatie.com for additional information.

To my dear wife Lori Jablonski

for her constant love and encouragement.

“To say that he is ugly is nothing, to add that his figure is grotesque

is to convey no adequate impression.”

— Edward Dicey, 1862

Contents

Introduction and Acknowledgments

Part One: Lincoln’s Entrance

Chapter 1: Lincoln Comes to Washington

Chapter 2: The Presidency

Chapter 3: The Rise of Party Politics

Chapter 4: The Spoils System

Chapter 5: The Slavery Debate

Chapter 6: Lincoln’s Nomination

Chapter 7: The 1860 Presidential Campaign

Chapter 8: Lincoln’s Election

Chapter 9: Lincoln in the Secession Winter

Chapter 10: The Flight Toward Compromise

Chapter 11: The Journey to Washington

Chapter 12: Lincoln and the Merchants

Part Two: Lincoln’s First Eighteen Months

Chapter 13: Lincoln’s First Impression

Chapter 14: The First Inaugural

Chapter 15: The Struggle with Seward, Then Sumter

Chapter 16: The Capital Surrounded

Chapter 17: The Hundred Days to Bull Run

Chapter 18: The Rise of the Radical Republicans

Chapter 19: The Phony War of 1861

Chapter 20: Democrats Disappear

Chapter 21: A Military House Divided

Part Three: Lincoln’s Proclamation

Chapter 22: Lincoln, Race, and the North

Chapter 23: Lincoln Awaits a Victory

Chapter 24: Emancipation Promised

Chapter 25: Emancipation Rebuked

Chapter 26: Emancipation Proclaimed

Chapter 27: The Rise of the Copperheads

Chapter 28: Lincoln Addresses the Nation

Part Four: Lincoln’s Reelection

Chapter 29: The 1864 Republican Nomination

Chapter 30: The Fall and the Temptation

Chapter 31: The 1864 Election

Chapter 32: The War at the End of the War

Epilogue: The Sudden Saint

Sources and Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction to New Edition

It is the widely-held conviction of every election year that modern political campaigning is a creeping poison, more negative than ever. “Politics was never so mean!” is the common cry. The corrective for this view is a study of the campaigns against Abraham Lincoln.

From the moment of his election, Lincoln had to contend with the people’s distrust of any authority. The Presidency, especially, was held in contempt by a public disgusted over the ravages of the Spoils System and rampant political corruption. The Founding Fathers—Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe—had given way to mediocrities—Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan. For many, this recent string of watery presidents seemed to have its bitter culmination in “The Railsplitter,” the anonymous man from the prairie who had never administrated anything larger than a two-person law office.

When he arrived in Washington, as a result of his awkward manners and his complete inattention to social convention and outward appearance, Lincoln had to battle the common prejudice concerning how a great man should look, act, and talk. Particularly among the elite, there was a shaking of heads after meeting Lincoln for the first time. The high-bred fastidious men of the East were aghast: How could anyone so ungentlemanly possibly be a statesman?

Even before he took office, president-elect Lincoln was at odds with those who regarded the states as sovereign powers, men who believed that every state had the right to dissolve the Union when the result of a national canvass did not serve its interests. Lincoln refused to concede this right, and maintained his conviction that the seceded states were not a separate nation but remained a part of the United States. And the war came.

From the war’s outset, Lincoln became the foe of almost every member of Congress. That institution had enjoyed preeminence in government since the first days of the American democratic experiment, and Lincoln toppled it from its position of unrivaled power. From the start of the war, Lincoln made policy without consulting the lawmakers. The Union, with a third of its citizens in rebellion, faced an unprecedented threat, and to defend it Lincoln brandished emergency powers—some granted by the Constitution and some not. His most far-reaching policy, the freeing of the slaves, was made by proclamation—that is, by personal fiat—without Congressional approval. Two months after the Emancipation Proclamation, at the war’s midpoint, only two congressmen could be counted as pro-Lincoln.

Lincoln battled during the entire war with the Democrats in the North—the “conservatives” of the time—who wanted to retain slavery and return the country to its prewar condition. The Democrats had held sway since Jefferson, and Lincoln’s election to the presidency at the head of a regional party had interrupted their firm hold on power. As Lincoln’s outrages against the precedents of the past continued, as casualties mounted in the Civil War and sorrow was piled on sorrow, Democrats’ voices grew increasingly strident: He was the “despot” Lincoln, the “tyrant” whose insistence on war and emancipation would destroy their America.

Lincoln, however, did not need to look as far as the rival party for enemies. He was wounded even more deeply by those closest to him, the Radical Republicans—the “progressives” of the time, and the strongest wing of his own party—who were as much convinced of Lincoln’s malignity as the conservative Democrats. Lincoln, the man in the middle, the man who waited, the man who heard all sides, could never be one of them. They reviled Lincoln as one whose heart was not in the holy work of freeing the slaves, and they sharpened their knives for him, even at the same time the Democrats were loudest in their woe.

Lincoln, too, fought his generals for most of the war.

Some of them, like John Charles Fremont, were radical Republicans; some, like George McClellan, were conservative Democrats. All resented his interference. Lincoln’s battle with the men in epaulettes would not turn decisively until the summer of 1864, when Lincoln placed Ulysses S. Grant at the head of the army in the East and William Sherman in the West.

Lincoln’s response to his political enemies in the press, the Democratic newspaper editors, was unapologetic and fierce: He stopped their presses and put them in jail. They replied with acid-dipped pens, and daily published the most brutal vitriol in the history of American public discourse, even calling for his assassination.

The domestic battles in the North could not be fought by a man unfamiliar with, or squeamish about, the blunt use of political power. To preserve the nation Lincoln needed to be, and was, the ultimate politician; that is, a master of the art of the possible. His battles with his public foes were fought with hardedged political weapons in a way that was possible only in mid-nineteenth century America in the rough-and-tumble heyday of bare-knuckled politics.

Larry Tagg

October 2012

Introduction

The Abraham Lincoln most Americans know today is a marble man, a mythic icon enshrined in a magnificent twenty-foot tall statue that looks down on visitors from beneath the dome of his Memorial, a Greek temple modeled after the Temple of Zeus.

One shibboleth of the Lincoln myth is the sentimental notion that he was the idol of the common people during his presidency. Unfortunately, the evidence for Lincoln’s popular appeal is missing. Rather, he suffered from an almost unbroken series of failures to win the favor of the press, the public, and the nation’s leading men.

The reasons for his unpopularity started with the wretched plight of the presidency itself as he took it up. Lincoln was inaugurated in an era when the presidency was tarnished by the string of poor presidents who preceded him, at a time when all authority was little regarded. The future of democratic government was itself in doubt, even by Americans. The torsions of the slavery debate and attacks by the rabid press routinely destroyed the reputations of public men.

Lincoln appeared on this stormy national scene virtually unknown except as a caricature, the Railsplitter. The people of the South saw the anonymous Illinoisan as a usurper, the illegitimate product of an electoral system that had betrayed the vision of the Founding Fathers. The people of the North feared the political machinery had lifted up a man woefully unequal to the national crisis. From his election by an absurdly low 40% of the electorate—lower than almost every loser of a presidential election in every two-party race in American history—his approval dropped to 25% by the time he took office, as state after Southern state showed its rejection of his legitimacy by leaving the Union, and nervous Northerners backed away from his uncompromising opposition to slavery’s expansion. When he arrived in Washington in late February of 1861, he did so on a secret night train to avoid assassination; the scathing reaction of the national press to his undignified entrance mark the days before his inaugural as the historic low point of American presidential prestige.

From this poor start, Lincoln sank lower in the eyes of Washington leaders when they beheld at first hand his ungrammatical language, his Western diction, his uncouth ways, his awkward gait and posture, and his penchant for coarse humor. A certain manner was expected of earnest statesmen, and Lincoln disappointed those expectations completely. It was hard for men of the East to comprehend that such a man, with such vulgar habits, could ever be great.

His first proclamation six weeks after his inauguration, in which he called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the uprising signaled by the firing on Fort Sumter, precipitated the loss of Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas, doubling the size and the population of the enemy Confederacy. During the first eighteen months of the Civil War that followed, his hesitant performance seemed to confirm the opinion of the many who saw him as an untutored rustic, hopelessly unequal to his task. As the dead piled up in unimaginable numbers and sorrow was added to sorrow, a nation that had known little of sacrifice blamed Lincoln for a dithering mismanagement of the war effort.

When, in September of 1862, he announced his intention to issue an Emancipation Proclamation one hundred days later, the Northern electorate showed its displeasure by rebuking him in a mid-term election so disastrous that a friend wrote, “I could not conceive it possible for Lincoln to successfully administer the government and prosecute the war with the six most important loyal States declaring against him at the polls.”

When the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, resulted in the freedom of not one slave, its lack of efficacy discouraged the abolitionists at the same time its revolutionary spirit threatened to take the intensely Negrophobic states of the Old Northwest out of the Union. The revolt of the North’s Lincoln-haters in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Federal Draft Law in March 1863 had its fiery culmination in the riot in New York City the following July, the largest civil insurrection in American history apart from the Civil War itself.

By 1864, Lincoln was so little regarded that the strongest elements in his own party tried to deny him another term. He engineered his renomination by stacking the Republican convention with appointees, a tactic possible only in the heyday of the Spoils System. As late as two months before the 1864 election, even Republican leaders wrote him off as a beaten man, and took steps to nominate a better candidate. Only by the combination of Democratic bungling and the miracle of last-minute Union victories on the battlefield was Lincoln reelected. As Ohio Republican Lewis D. Campbell observed, “Nothing but the undying attachment of our people to the Union has saved us from terrible disaster. Mr. Lincoln’s popularity had nothing to do with it.” Anti-Lincoln feelings hardened in the days after his reelection, as bitter Democrats and vanquished Southerners looked with dread on the prospect of another four years under “the despot Lincoln,” a period that climaxed with Lincoln’s assassination less than a week after the surrender of Lee’s army.

The most sensational aspect of the criticism Lincoln endured was the unsurpassed venom of it. The press was unashamedly partisan, and in a historical era dominated by Democrats, most newspapers were Democratic, duty-bound to wound the Republican leader. There was much to criticize. During the Civil War’s four years of unprecedented danger to the Union, they called Lincoln a “bloody tyrant” and a “dictator” for stretching the rules of the Constitution to allow arbitrary arrests, the suspension of habeas corpus, and the suppression of newspapers sympathetic to the Confederacy. Lincoln’s greatest outrage, however, was that he took his place so resolutely at the center of American opinion during the bitterest time in the nation’s history. As a man of caution and moderation, he was blasted from all sides by a Northern people whom the heat of battle had driven to political extremes.

If one considers politics as the art of the possible, Lincoln was the consummate politician. What he accomplished is all the more remarkable considering how limited his possibilities were as a result of his lack of esteem. The depth of Lincoln’s travail is much of what ennobles him. To have a fuller knowledge of the bitterness of the opposition Lincoln faced is, in my view, necessary to a fuller appreciation of this most intriguing of presidents, whose humanity is, if anything, trivialized by being so bronzed over. While researching my book, I have been amazed that the story of Lincoln’s unpopularity has remained so long untold at full length. It is better that it be so told, in order that we may better understand the man.

Larry Tagg

January 2009

Acknowledgments

Many people played roles large and small in helping me research this book. One man in particular was Harold Holzer, one of the world’s leading Lincoln scholars. Mr. Holzer was generous with his time in sharing with me knowledge of Lincoln’s humor and directing my searches in the large Lincoln bibliography. I am forever in his debt.

I am also deeply indebted to Captain Rob Aye

r of the United States Coast Guard Academy for his superb developmental editing of my manuscript, his keen insights, and his confidence in my work.

It has been wonderful to work with my publisher Savas Beatie LLC. Managing Director Theodore P. Savas saw value in my manuscript early in its development. He provided constant support, demonstrated a painstaking attention to detail, and offered invaluable advice coupled with his tireless energy to help produce the book you are now reading. I had worked with Ted more than a decade ago on The Generals of Gettysburg, and it was good to work with him again. I am also indebted to Marketing Director Sarah Keeney for her continuing help in getting the word out about the book. Sarah understands marketing and publicity, and is always available for a phone call or email exchange. Veronica Kane and Tammy Hall have been working hard with Sarah to coordinate a book signing and speaking tour, and use all the new Internet technologies now available to authors to help promote books like mine. I am in very good hands.

I also owe a great debt to David Van Dusen for his technical expertise and artistic skill in creating the book’s dust jacket, its accompanying website at www.larrytagg.com, and for producing the book trailer.

Hearty thanks are also due Brent Bourgeois and my wife Lori Jablonski for reading the manuscript and offering their invaluable comments during its long development.

Part One

Lincoln’s Entrance

“What Brought Him Here So Suddenly?”

Chapter 1

Lincoln Comes to Washington

“We feel humiliated to the last degree by it.”

On February 23, 1861, nine days before his inauguration, President-elect Abraham Lincoln sneaked into Washington on a secret night train, disguised in a soft felt hat, muffler, and short bobtail overcoat. Detective Allan Pinkerton, who traveled with him, provided the affair with a cloak-and-dagger coda when he telegraphed Lincoln’s friends: “Plums arrived here with Nuts this morning—all right.”

The Battles that Made Abraham Lincoln

The Battles that Made Abraham Lincoln